Henry Ford was an extraordinarily wealthy man with a tremendous grasp of systems. He started out with a lathe in a shed on a farm. With it, he learned to build a car. So did a couple of dozen other people in the same period. Ford, however, had the best sense of systems.

He knew, for instance, that he had to buy components. Some of those components were wooden floorboards. To reduce costs of floorboards to zero, he required a supplier to pack Ford components in a wooden box with exact dimensions. When disassembled, those boxes produced six pieces of wood which would perfectly fit in his automobile as floorboards. Free floorboards.

Over time, he opened his own iron mines, built his own coke furnaces, used the coke waste as foundry material, the heat from making coke to generate electricity, and the coke, itself, to make steel. He owned forests, sawmills, chemical companies, and effectively controlled every source of supply that he could.

Doing this allowed him to do something that few manufacturers have done since: he made automobiles as inexpensively as possible and used the economies of scale to continue driving down the price. His Model T, with no changes, got cheaper to make every year as ever fewer workers were needed to manufacture them. Workers in the Model T plant were encouraged to take the summers off to engage in agricultural activities, which he thought would make them “well-rounded”.

Soon, competitors forced annual model changes, along with “sissy” improvements like shock absorbers and electric starters. Adding those things, along with yearly model changes and improvements, made Fords more expensive, and workers worked year ’round. Rather than paying cash for a simple Model T, consumers went into debt to buy more expensive automobiles, and lots of things in America changed.

Fordlandia

Ford’s drive for control compelled him to develop his own sources of rubber. He went to Brazil, obtained a piece of land the size of Delaware, and sent executives to build the new capitol city of his proposed rubber empire, Fordlandia.

The executives were to hire crews, clear the jungle, and plant rubber trees. Despite spending millions, mostly on infrastructure like schools, roads, homes, docks, railroad, power plant, water system, sewers, and a hospital, his plans failed to produce. The whole operation had to be shut down. It was just too difficult to build a large Electrical Age corporate structure on top of a Stone Age foundation.

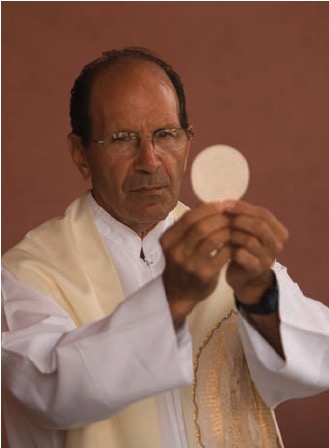

Centuries earlier, Jesuit missionaries built huge missions in South America. They, like Henry Ford, had a great sense of systems. They could teach the local Indians to do almost anything. The Jesuits lived purely in the Iron Age, not far from the late Stone Age in which the Indians had been raised. This cultural gap could be bridged so well that the Indians in at least one of their missions learned to make pipe organs, one of the most complicated things of the period. They envisioned that Jesuit missions would become “economic islands of social justice”, with communities centered around large churches. Many Eden-chasers in The Church look back at their efforts, and sigh in disappointment at their failure.

Such missions were frowned upon by The Church hierarchy. Those who understood that the mission of The Church was to save souls, not focus on the easier, and for many, more self-rewarding work of inventing alternative economic and social systems, were glad the missions withered away. The same thing that happened to them was revisited upon Fordlandia.

Just as “We are here to save souls, not try to make Heaven on Earth.” finally came down from the hierarchy; centuries later, Ford Motor decreed as their own attempts to remodel society failed, “We are here to make cars profitably, not to restructure the Amazon’s society and economy.” Both the decaying missions and the overgrown remains of Fordlandia are still visited, often by the kind of people who always say, “If only . . . . . “, expressing the near-universal Utopianism that is the hallmark of those who would play God.

Nowhere have they succeeded.